6MK is an exhibit of original portraits of Holocaust survivors drawn by Mia Kamensky. Each unique work of art includes a QR code linked to the survivor’s miraculous story.

Click on each image to see the survivor’s story

Unlike other pieces included in 6 Million Known, this is not a portrait of a Holocaust survivor. Instead, this work represents the shock and horror Jews are experiencing as we navigate life in a post-October 7 world.

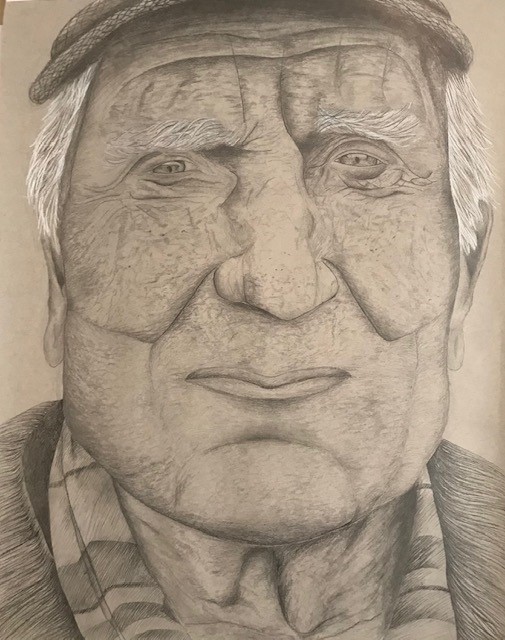

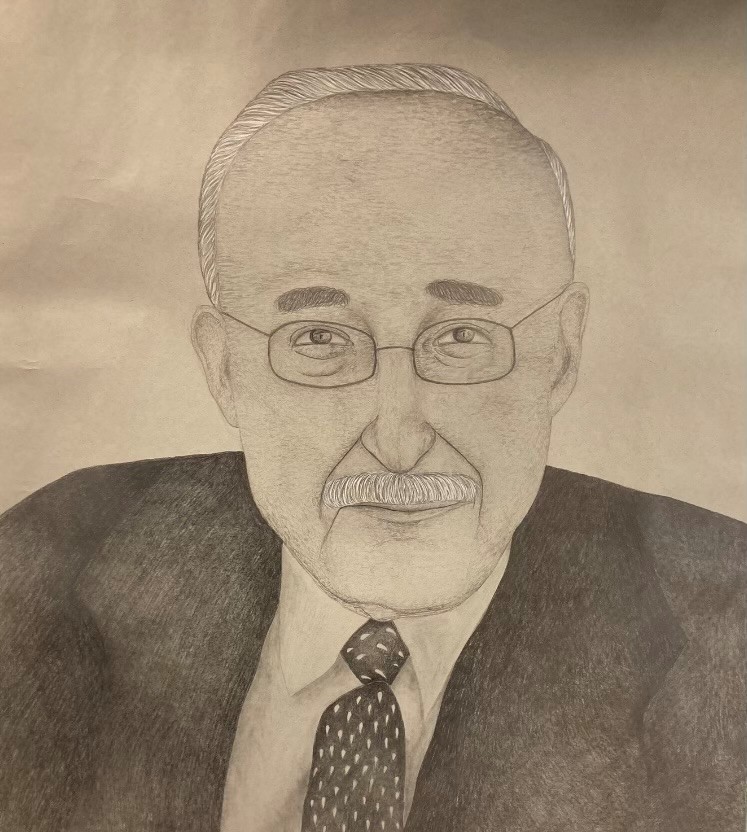

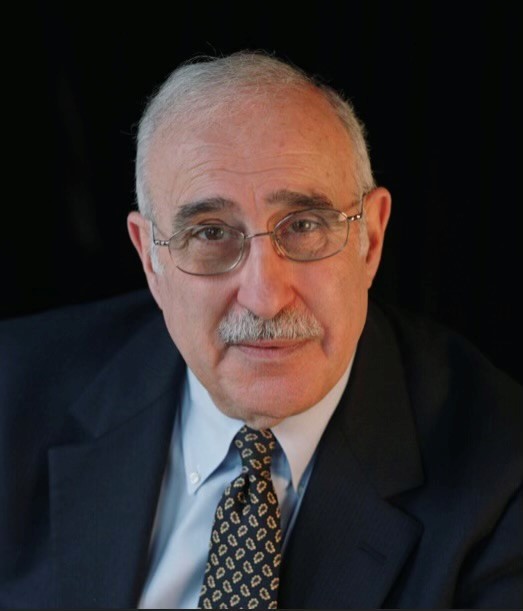

Werner was born in a suburb of Berlin, Germany on October 1st, 1927.

When Werner was 6 years old, his family moved from Berlin to Yugoslavia. His early years were happy ones. He loved to read, eat noodles, collect stamps, and play marbles with his friends. He had a diverse group of friends who hailed from a variety of religions. Werner did not experience any antisemitism as a child until right after his Bar Mitzvah when the Nazis came to power. That was when he started wearing the yellow star in the front and back of his clothing. “You couldn’t really hide the star by crossing your arms over the front of your shirt, so people used to push you, throw garbage at you,” he recalled.

Given the danger on the streets, Werner’s mother feared for his safety and arranged for him to live with a non-Jewish couple. He stayed with this kind family between the ages of thirteen and fifteen. One morning, there was banging on the door of the non-Jewish couple’s home. It was the German secret police. An officer pointed a gun at Werner and held a gun to his back as he used the restroom. The officers assaulted him and locked him in a bug-infested basement cell that was bare except for a bucket to use as a toilet. One day, while trapped in this basement cell, Werner looked out a barred window and saw his mother walking on the street. He hadn’t seen her for two years and though he waved to catch her attention, she did not see him and continued on her way down the street. That was the last time he ever saw his mother.

After spending six weeks in the cell, Werner was sent to Vienna where he found himself in a beautiful synagogue that had been destroyed during Kristallnacht. Glass shards littered the floor and torn prayer books and prayer shawls were saturated by water. “It was a mess,” he said. “The seats were all torn and cut up.”

Eventually, the SS put Werner on a train and he spent two days traveling to Czechoslovakia under Nazi supervision. He entered Terezín, a work camp where he laid railroad tracks. Terezin grew overpopulated with the innocent Jewish prisoners, so Werner was sent on a tightly packed train car to Auschwitz, a death camp or extermination camp. “For the next three days we were lying in our feces and in our urine and some people died in our car,” he remembered. “It was basically hell.” In Auschwitz, the SS officers had skulls and crossbones on their lapels. The Jews were tattooed with numbers and had absolutely nothing. “Doctors” would come in just to kill people and break their arms and back and legs. Food bowls were filled in the morning with brown water made out of acorns and they received two ounces of bread made out of flour and sawdust. In the afternoon or evening they received “soup” – salt water with tiny pieces of unwashed dirty potatoes – and maybe another piece of bread. They slept in barracks that often collapsed and killed those resting on the lower levels. Werner shared a barack with a man named Mr. Levine who was a magician and kept a deck of cards with him. Mr. Levine taught Werner magic tricks while they were in Auschwitz and for the rest of Werner’s life, he practiced magic.

Werner survived until liberation. He walked out of Auschwitz when he was 17-years-old. He weighed only 64 pounds. He had no family and no belongings. He hitchhiked a train back to Yugoslavia and entered his new life as a free man wearing the clothes of a deceased man.

Eventually, Werner moved to England where he worked as a machine tool picker and a dye maker. He married and relocated to the United States where he worked during the day and attended college at night for ten years. Ultimately, he became an industrial engineer, a father to two sons, two daughters-in-law and grandchildren.

Werner spent decades speaking to schools where he shared his remarkable life story.

Unfortunately, Werner passed away July 8th 2022. He was 94 years old. He leaves behind a beautiful and inspiring legacy.

To know more about Werner, click here:

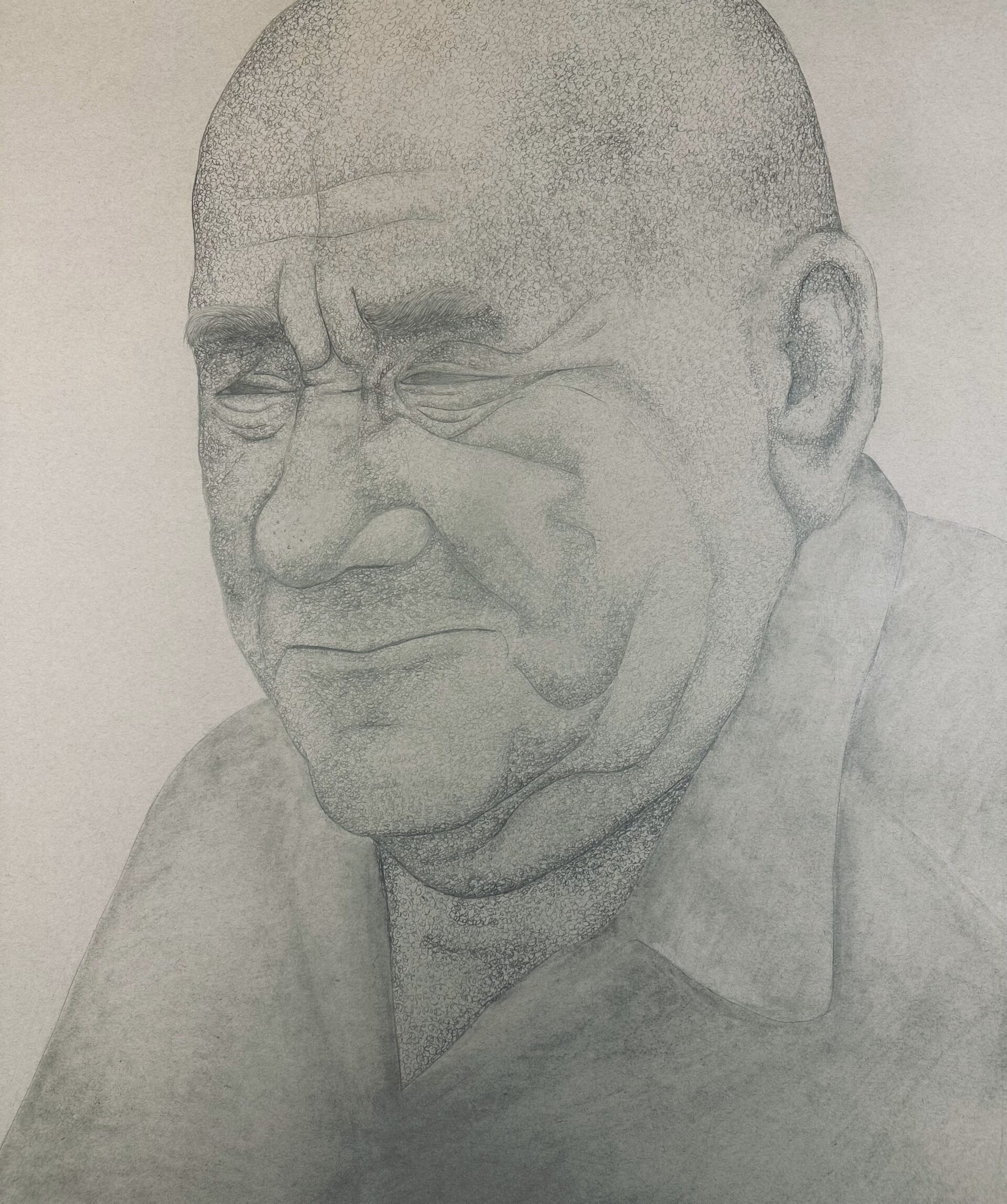

Mark was born in Russia in 1930. He was a pilot in the Russian army for 39 years, including during World War II. He immigrated to Israel about thirty years ago with his wife, Nina, and son. He now lives in Jerusalem and reminisces about his time as a pilot.

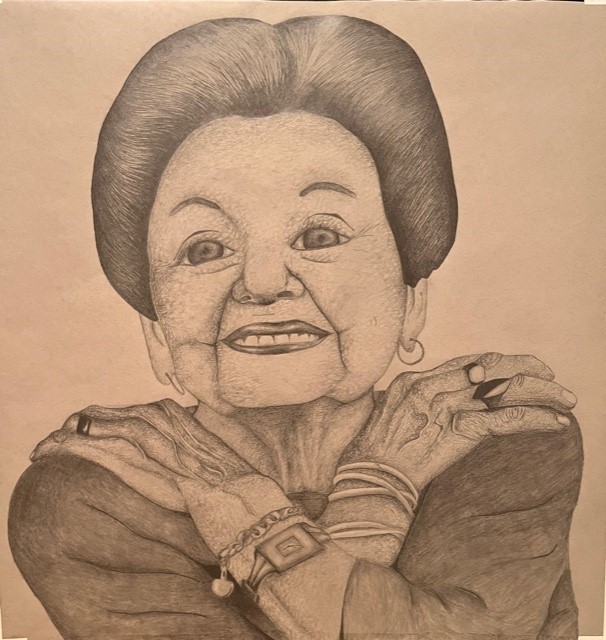

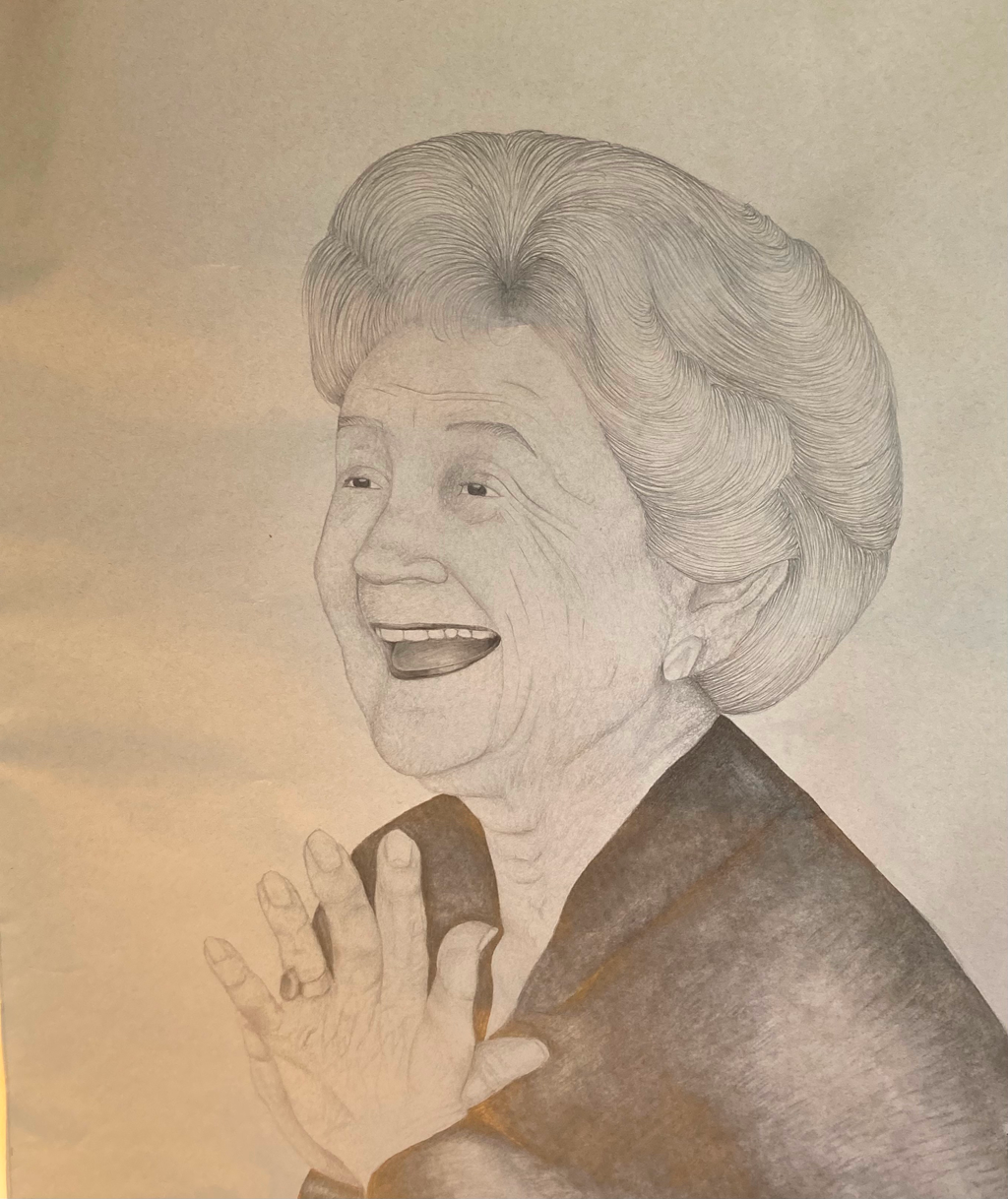

Rachel Epstein was born in Compiegne, France on April 29, 1932, and became a victim of the Nazis when she was just a young girl. In 1939, when the Nazis invaded France, Rachel’s father’s business was taken away from him and her family lost their personal possessions because they were Jewish. They had to wear a yellow star on their clothing at all times. Rachel’s father was arrested, her parents were taken to Paris, and Rachel never saw them again. A non-Jewish family adopted Rachel and her brother. This family kept them safe and loved and treated them as if they were their own children.

When the Nazi regime became more dangerous, Rachel and her brother had to escape for safety. The entire family decided to temporarily flee together. Once it was safe to return to France, they learned that Rachel and her brother were at the top of the Nazis’ list to take to the concentration camps. A Nazi officer accidentally spilled coffee on the list and it covered Rachel’s name and her brother’s name. They were saved.

They stayed in France with their adopted parents until the end of the war. When Rachel was fifteen, she and her brother became the legal children of their adopted parents. Rachel’s adopted uncle was living in Brooklyn, NY, and so Rachel traveled alone by boat at age sixteen to live with him and have a better life. Her younger brother stayed in France, and 13 years later, they reunited.

After moving to Brooklyn, Rachel met a boy named Isidore Epstein. At first, they could only communicate in Yiddish, but he soon taught her how to speak English. They got married when she was 18 years-old and eventually had two daughters. Now, she has four grandchildren and one great-grandchild. She is forever grateful to her adopted parents for their love and all they sacrificed.

A documentary was made about Rachel’s story and her life with her adopted parents: “17 Rue St. Fiacre.” Now, Rachel lives on Long Island with her husband Izzy. Izzy loves to invent new technological inventions and Rachel loves to dance. She especially enjoys Argentine Tango, ballroom dancing, and tap dance.

To learn more about Rachel in her own words, click here.

Minna does not wish to share her story. It is important to remember that these survivors underwent traumatic experiences. For some, retelling their stories is too painful. It is imperative that we recognize and respect their choices.

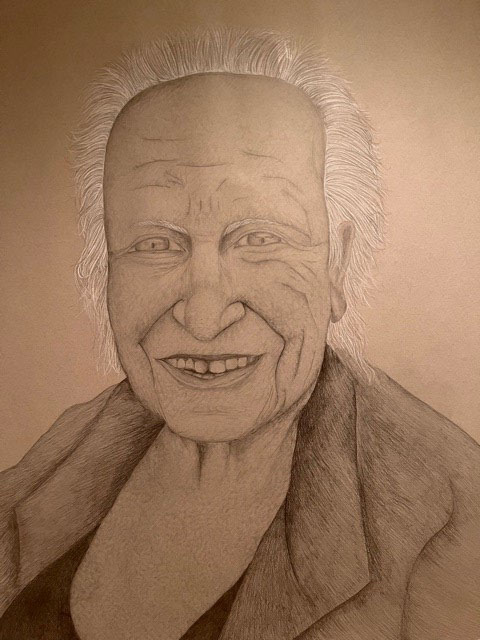

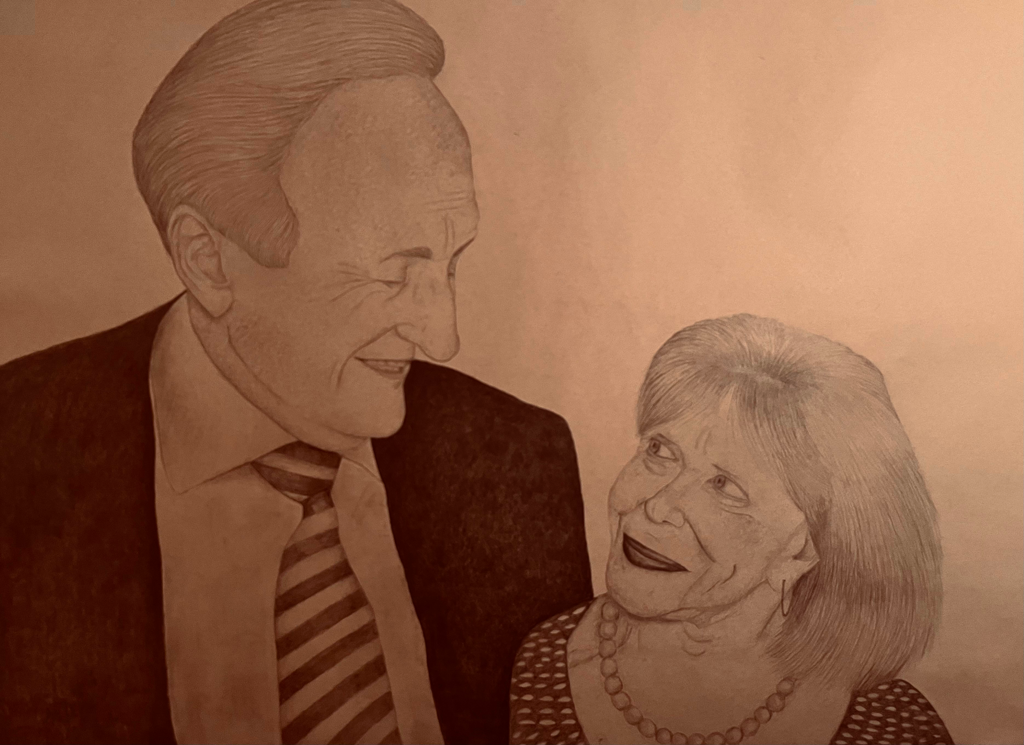

Eva and Les Sanders were both born in Budapest, Hungary in the early 1930s. Growing up, Eva loved to play cards with her father, and as a teen she was very involved in the Zionist youth movement. She met Les in grade school where they had mutual friends, but did not start dating until they were in university and both studying engineering. One day they left a water-polo match together, and the rest is history. They are married 67 years and counting.

Much of their childhood was filled with antisemitic events. Violent pogroms would beat Jews walking along the streets, and Jewish stores, businesses and synagogues were destroyed. Les’ father was subject to multiple incarcerations simply for the crime of being a Jew who owned his own business. He disappeared in the night to prison several times before WWII (as well as after under Communist rule), leaving young Les, his mother and brother frightened and alone.

In 1941, when Les was 9, and Eva was 7, both their fathers, and Les’ older brother, were taken to work in slave labor camps known for working men to death. By 1944, at ages 12 and 10, Hungarian law required young Jews, including Les and Eva, to wear a Yellow Star so that they could be tracked and easily targeted for persecution. Their families were required to move into overcrowded quarters. Eva’s family was forced to live in a building designated with a large Jewish Star for Jewish-only housing. Similarly, Les’ family was obligated to live in a Jewish-only building at first, and then later in the ghetto (buildings meant for 10,000 now held 60,000).

While her father was in the forced slave labor camps, Eva remembers the terror of the daily “selections” in the courtyard of the designated Jewish building. These selections conducted by the Hungarian Nazis were to separate the masses that would be marched to the Danube where they would be shot dead into the river or taken to perish in Auschwitz. While these happened daily, Eva’s childhood memory highlights one occasion when her mother’s quick thinking saved them both. Her mother realized, perhaps by intuition, or perhaps by noticing the elderly and weak among them, that their line would be those selected for the day’s mass murder. She took the risk, grabbed Eva, and deftly hastened them to the other line, saving both their lives. Among all the trauma Eva endured, this moment of her mother’s keen courage stands out among the many times her mother risked everything to save her young daughter from the atrocities that pursued them.

For a period Eva was alone as a child in a protected building run by the Red Cross for children, until her mother convinced someone on a cargo bike to retrieve her so they could reunite. At some point her father managed to escape the slave labor camp (as eventually did Les’ father and brother as well), and he joined them in one of these protected buildings. They were among the very lucky few who escaped deportation to concentration camps, or being shot into the Danube, onsite, or otherwise slaughtered as so many of their family, friends and neighbors had been. Eva lost many extended family members to the genocide of the Holocaust.

Les’ mother also acted fearlessly when deportations began in their Jewish building. She shielded her son as she found hiding place after hiding place for them. In his memoir Les recalls:

“…many Jews fled from the designated Jewish buildings to escape deportation, my mom and I among them. But where shall we go? According to Hungarian law each person had to register with the police where they lived, even overnight stays were supposed to be registered with the nearest police station. Food ration cards were issued to the person’s permanent residence, without ration cards food stores or restaurants wouldn’t serve you. Non-Jews were severely punished for sheltering Jews. Even if some decent person let us stay in their homes one or two nights, we had to move on to somewhere else, otherwise we risked arrest and jeopardized our benefactors. As a result we were hiding in numerous locations… There is no question in my mind that the Shoah could not have happened if the Jews had at that time a state of their own—Israel. Please think about that, our children, because the story is not over and Jews do not lack enemies even in our time. May you and your children live in a better world (which I’m afraid may not come soon), but remember your parents and grandparents history to fortify yourselves for a better life.” Les, like Eva, lost many friends, neighbors and most of his family to the Holocaust. His father had been one of 16 siblings. The majority of those 16, and their families, perished in the Holocaust. Les and Eva immigrated to the US in 1957 after a harrowing escape from Communism during the Hungarian Revolution in 1956. Both Eva and Les are mechanical engineers, and founded their own successful engineering and architecture firm Ener-Sol Associates. They raised a son and daughter in a traditional Jewish and Zionist home in Jamaica Estates, NY, and are proud grandparents to 5 grandchildren and 1 step grandchild. Les has been filmed in 2 Holocaust documentaries, including Names Not Numbers, and both he, Eva and their children continue to tell the stories of their family’s survival.

Rena Quint was born as “Fredzia Lichtenstein” in 1935 in Piotrkow Tribunalski, Poland.

In 1939, when Fredzia was three years old, the Nazis invaded and occupied her hometown.

In 1942, her mother and brothers were sent to Treblinka, a concentration camp, where they were murdered. Fredzia and her father were directed to another concentration camp where she pretended to be a boy in order to survive. Eventually, Fredzia’s father was killed and she was transported to Bergen-Belsen where she remained until liberation.

Orphaned, alone, and without a coat, shoes, or food, Fredzia was taken to a hospital and displaced persons (DP) camp and ultimately to Sweden. It was there, in Sweden, where she was introduced to a German survivor named Anna Philipstahl whose daughter had recently passed away. Fredzia assumed the identity of Anna’s deceased daughter. Suddenly, Fredzia became known as “Fannie” who had been born in Germany in February, 1936. Fannie used this name and documentation to travel to the United States with her new mother and new brother, Sigmund.

But only months after their new family arrived in Long Island, New York, Anna died. That was when “Fannie” was introduced to Leah and Jacob Globe, a childless couple from Brooklyn. In 1946, the Globes adopted Fredzia, and renamed her Rena – the Hebrew word for joy. They gave her everything she had lost during the Holocaust – a large family as well as a safe, loving home. Rena learned English, attended a Jewish day school, and earned her bachelors and masters degrees in education. She married, became a mother to four children, and worked as a teacher before becoming a lecturer at Adelphi University and at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. In 1984, Rena and her husband immigrated to Israel where some of her children and her adopted mother, Leah Globe, had settled. They built a beautiful home in Jerusalem where she continues to live to this day. Rena has volunteered teaching English to Russian immigrants and has spent decades working as a docent at Yad Vashem – The World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem. In 2017, she published her memoir, A Daughter of Many Mothers, and continues to share her life story through speaking engagements. In July, 2022, Rena was one of two Holocaust survivors to meet with President Joe Biden when he visited Yad Vashem.

Maya was born in 1940 in Kiev, Ukraine, and was only a year old when the Holocaust began. Her father was a doctor for soldiers so he worked in war hospitals, while her mother stayed home and cared for her. When the war broke out, Maya and her mother fled to Siberia while her father continued to care for sick soldiers. They were in Siberia for 4 years until the war ended. After the war, her parents met up in St. Petersburg and her father went on to pursue a career in academics. Though Maya was safe with her parents in St. Petersburg, they lost their entire family in the Second World War. In her adulthood, Maya worked for many years as a physics and math teacher in Russia before making Aliyah and working with children with special needs in Israel. She currently works in the ceramic workshop at Yad LaKashish which provides support services for elderly around Jerusalem, many of whom are Holocaust survivors. In her free time, Maya enjoys painting, creating ceramics, and practicing her English language skills.

Leo was born in July, 1939 in Amsterdam to a family of Dutch Jews. He had a wonderful childhood and a beautiful home. His father was German and worked in the diamond business. In 1940, after Hitler bombed Holland, Leo, his parents and grandmother went to a fishing point to try to escape Holland, but there were no boats. They made multiple attempts to escape, but eventually realized that they would never be able to leave because the Germans had sealed the borders. All Jews were forced into Amsterdam, so his extended family moved into his apartment. Jews were not permitted to attend public schools, visit parks, shop at grocery stores, dine at restaurants, have radios, and ride trains or cars.

The Nazis placed a “J” for Jew on all forms of identification for Jews. Jewish women had to have “Sarah” as a middle name while all men had to have “Simon” as a middle name. Yellow Jewish stars were forcibly sewn on the clothes Jews wore so they could be identified easily.

Leo and his family did not have many options for survival because England and the US did not accept Jews. His father wanted them to go into hiding. When the Nazis found his cousins, Leo’s grandma tried to bribe the Germans with diamonds, but his cousins were imprisoned and ultimately sent to a concentration camp in Germany.

In 1943, when Leo was 4 years old, his parents wanted him to go into hiding alone so that he could be saved. With the help of a priest, his parents gave him to the resistance movement while they hid in a different location. A Muslim rug dealer gave Leo’s father a Muslim prayer rug and told him to take it with him into hiding because it was good luck. Leo’s parents hid in an attic with no heat electricity and only one window. It was tiny and cramped and they did not have food, but they kept that rug with them. His mother left the apartment only once during those three years to visit a dentist. When the dentist laid eyes on her, he gave her a loaf of bread.

While his parents remained in hiding, Leo moved around. First, he lived with a retired policeman and his wife. They were good people. They didn’t know Leo, but knew that if this young boy were discovered, he would be killed. The couple cared for him and then placed him in an orphanage where he was ultimately taken in by a family from the suburbs with a seventeen year old daughter. Leo did not suffer. The family cared for him and he did not know that there was a war going on. Throughout this time, his parents were unaware of Leo’s whereabouts.

In May of 1945, the war ended in Holland and everyone celebrated by wearing orange to honor the Dutch House of Orange. With the help of the resistance movement, Leo and his parents were reunited, but reconnecting had its challenges. His parents were so emaciated they could barely walk and Leo did not remember or recognize his parents. When they returned home, he remained in touch with the family that cared for him. In time, Leo went back to school, his father got his job back, they moved into a house, bought a car and adopted a dog. Though it would seem their lives were full again, they were not because most of their friends and relatives had been killed. It was because of this emotional void that Leo’s family decided to come to America.

In 1947, Leo and his parents sailed to New York. As they crossed through Ellis Island, his mom said, “We did it! We beat Hitler!” They settled in Port Washington where Leo attended public school and learned English. His dad found a job at a store in Manhasset.

In 1961, Leo graduated from Harvard College. In 1964, he graduated from Columbia Law School and Columbia Business School. He served in the Marine Corps and the Marine Corps reserves between 1959-1965. Leo practiced law for over thirty years and founded highly successful real estate and management companies.

Leo is connected to Anne Frank’s family. He has hosted Anne Frank’s cousins at his house and he even helped bring her diary to the Dutch government, which would eventually become The Diary of Anne Frank. Leo served as a Director of the Anne Frank Center USA for two decades and as its Chairman for seven years. He has also served as the Chairman of the Foundation for the Jewish Historical Museum of Amsterdam. He and his wife Kay co-sponsored the exhibit State of Deception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda at the U.S. National Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, where he also served as a member of the Development Committee.

In 2015, Leo published a book about his life titled 796 Days: Hiding as a Child in Occupied Amsterdam During WWII and Then Coming to America.

Leo and Kay Ullman have four children, nine grandchildren, and live on Long Island, New York where he keeps the rug that was given to his father before their family went into hiding. The rug serves as a reminder of their family’s strength and perseverance. To this day, Leo is passionate about sharing his story. He lectures widely and hopes that through education history will never be erased.